The world was ‘shocked’ by the recent attacks in Paris, primarily directed at the offices of the satirical newspaper Charlie Hebdo, that left 17 people dead. The exceptionally heavy levels of media coverage throughout the world, the spread of the ‘Je Suis Charlie’ message of solidarity, and the attendance of leaders from 40 countries at a rally in Paris make this abundantly clear.

Prominent publications outside France, including the BBC and the New York Times, carried articles claiming that this attack signals a “new era of terrorism”. Media coverage has been concentrated and emotive, offering every last detail of the attack itself, the perpetrators and the victims, the manhunt, and of the outpouring of grief and solidarity, as well as editorials, opinion and extensive analysis on the implications of the attacks in terms of the issue of terrorism and freedom of speech. Newspapers carried headlines portraying the attacks as a “war on freedom”, and “barbaric”. The names, faces and profiles of the victims were shared with readers and viewers of the news throughout the world, from the US, to Japan and New Zealand. An article in the Times of India criticized the city of Kolkata for the low turnout at a rally to express solidarity with the victims.

The response to these attacks, however, was in stark contrast to the relative silence that met another set of mass killings in early January – a series of massacres focused around the northeast Nigerian town of Baga perpetrated by the rebel Boko Haram. After having overrun a military outpost in Baga, Boko Haram forces, attacking with rocket-propelled grenades and assault rifles, began killing everyone in sight in and around the town, including children and the elderly. The death toll at this stage is unclear. Initial estimates range from dozens to hundreds to as many as two thousand. But it is highly likely that this is the deadliest massacre ever perpetrated by Boko Haram.

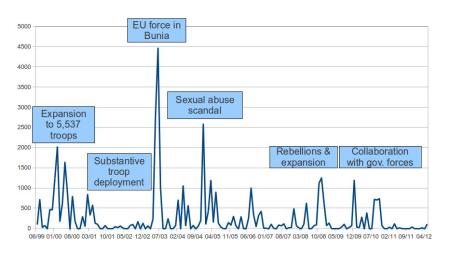

Given the scale of the atrocity, the muted media response is troubling to say the least. The New York Times offered just one article on the matter, titled ‘Dozens said to die in Boko Haram attack‘. The newspaper appears to have made no attempt after this article to follow-up, to confirm whether the death toll was indeed dozens, hundreds or thousands, to discover any further details, or to offer any opinion or analysis. The BBC published an online article in which a Nigerian archbishop criticized “the West” for ignoring the Baga massacre, particularly offering the contrast of attention to the attacks in France, but at the time the BBC itself had published only three online articles on the Baga massacre. Far from attempting to put names, faces and profiles on the victims, the media appeared uninterested in even counting them.

There has been very little in the way of expressions of concern from the public as a whole, or from political leaders outside the country. There have been no major public outpourings of solidarity and no “I am Baga” slogans on signboards or online that have managed to go viral. Given the lack of response by the media, it is highly likely that the events themselves are largely unknown to many beyond the region.

So what makes these two incidents so different? Why is one seen as heralding a “new era of terrorism”, and the other, not even deemed worthy of following up? As in Paris, civilians in Baga were specifically targeted and shot. As in Paris, the killers identified themselves as defenders of Islam against Western actions and influences. Indeed the name Boko Haram roughly translates as “Western education is forbidden”, and the group has expressed its support for the Islamic State. And while great care needs to be taken in using the term ‘terrorism’ (given the subjective political baggage it inevitably carries), the events in Baga, Nigeria, were as much acts of terrorism as were the attacks in Paris, France – both involved the deliberate use of violence against non-combatants to intimidate the general population with a view to achieving a political objective.

One major difference between the atrocities is clearly the fact that while the civilian victims in the Baga massacre were targeted en masse, the civilians targeted in the Paris massacre were primarily media personnel (albeit from a particular media publication). This gave the attention to the Paris massacre the additional angle of the attempted intimidation of journalists. It must also be said, however, that this is a constant and global issue of concern. Threats by Boko Haram against journalists are part of the reason why the conflict has tended to attract little media coverage to begin with. Throughout the world in 2014, a total of 96 media personnel were killed, seventeen of whom were killed in Syria. The fact that the eight media personnel killed in Paris were killed in a single incident does of course make this case significant. But the 2009 killing of 32 media personnel in a single incident in Maguindanao, Philippines, along with a number of politicians (that the journalists were accompanying) and other civilians, did not result in a fraction of the attention, coverage or outrage on a global scale that we see now. Foreign news corporations did not categorize the incident as representing a “new era of terrorism” or a “war on freedom”, and the attacks sparked little debate about the importance of protecting journalism from intimidation and the challenge to freedom of speech.

Hypothetically speaking, had the roles been reversed – had an attack on a satirical newspaper office in Nigeria resulted in 12 deaths, and had an attack on a town in France at the same time left hundreds dead – we could safely predict that the events in France would still have attracted the vast majority of the attention and the indignation, and that the threat of intimidation against journalism would simply not have been a major issue for debate.

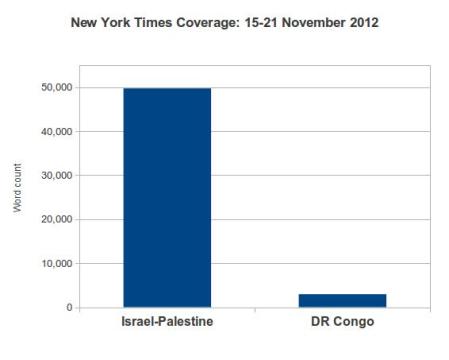

The real reasons for the differences in the coverage are less related to what atrocities were perpetrated, and more related to where, and against who, the atrocities were perpetrated. Numerous studies (like this book and this journal article) have shown that the raw number of deaths from conflict, crimes and atrocities is unrelated to the quantity and intensity of media coverage that rises in response. Factors such as the race and socioeconomic status of the victims, among others, have a much greater bearing on the levels of coverage an atrocity can attract. It is a sad reality that, for news corporations in the West (including distant Australia and New Zealand) the perceived newsworthiness of black impoverished Africans is far less than that for white Europeans.

Having said this, access to the scene of the atrocities is undoubtedly also a major issue. Baga is a remote town in Nigeria, and is currently under the control of Boko Haram. For all of the advances in information and communication technology, as a general rule, reporters still have to be able to physically reach the place in question to collect footage, images and interviews, in order to reliably report on the situation. But in the case of Baga, reporters can still reach the survivors who fled, and others displaced by the conflict. That they have not, on the whole, attempted to do so, is a reflection on the lack of perceived newsworthiness of the atrocity for other reasons. And the minimal presence of Western reporters in Nigeria to begin with, is also a reflection of the chronic lack of perceived newsworthiness regarding the region in a historical sense.

The fact that the massacre in Baga was not the first by Boko Haram, and that it took place in a conflict situation, must also be considered as a difference to the massacre in Paris. The newsworthiness of an atrocity tends to quickly decrease if it is a reoccurring one. But reoccurring conflict in Israel-Palestine under similar circumstances has never been a barrier to consistently heavy media coverage. And the fact that the Baga massacre is the deadliest in the history of Boko Haram should give the media pause to reconsider its relative indifference. Further recent atrocities, like the use of a girl as young as ten years old by Boko Haram as a suicide bomber in a marketplace in a different town in northeast Nigeria, should also carry a certain newsworthiness. If the coverage to date is any indication, they have not.

There is no question that the need to protect journalists from intimidation is an important and valid concern. It is crucial that we work towards realizing a world in which the pen is mightier than the sword, and in which the sword is not used in response to the pen. But at the same time, we should also work towards realizing a world in which the pen is not so selective in who it chooses to write about, particularly when so many lives are at stake.