I recently had the pleasure of receiving correspondence from Professor Andrew Mack, director of the Human Security Report Project at Simon Fraser University in Vancouver. The Project produces the Human Security Report, the most recent one being the “Shrinking Costs of War”. This report has generated quite a debate over its claim that the death toll in the DRC is not nearly as high as the 5.4 million estimated by the International Rescue Committee.

I had commented elsewhere on the issue, and Professor Mack invited me to take a look at the Overview of the Debate that the Project had put up on their website. The following exchange followed. The main text is what I wrote, and the sections in CAPS are the responses from Professor Mack.

VH: “Although not able to comment on the methodology of either the IRC methodology or that of the Human Security Report, I see the points you are making, and can understand the huge difference that a small change in baseline assumptions can make in the final tally.

From my perspective, I had a problem with the “paradox of mortality rates that decline in wartime”. I can certainly understand that advances in child health are being made despite the presence of conflict in a part of a country, and that the means of waging war are less destructive than they have been in the past, but I don’t think that this situation is a paradox, and found the notion a bit misleading.

AM: PRESENTED WITH THE STATS MANY PEOPLE DO THINK ITS A PARADOX — LARGELY BECAUSE THEY DON’T REALISE WHAT A HUGE DECLINE THERE HAS BEEN IN CHILD MORTALITY IN PEACETIME AND THAT TODAY YOU NEED A VERY BIG WAR TO REVERSE THE TREND..WE ACTUALLY SAY IT ISN’T REALLY A PARADOX.

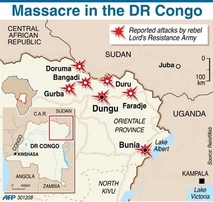

VH: I think it’s somewhat unfair to compare national statistics on mortality and then use those results to say that “mortality rates decline in wartime”. The units of analysis are quite different. As noted in the report itself, the area of conflict and the national borders are not the same thing and can be quite different – the DRC, with a total square area the size of Western Europe, but with a conflict zone largely limited to the Kivus and Ituri, is a case in point.

AM: THIS IS ONE OF THE POINTS WE MAKE — WARS ARE NOT ONLY SMALLER BUT ALSO MORE LOCALIZED… BUT OUR POINT––THAT NATIONWIDE WAR TOLLS HAVE DECLINED DRAMATICALLY IS AN IMPORTANT AND LITTLE RECOGNISED ONE.

IT IS OF COURSE TRUE THAT MORTALITY RATES IN WAR ZONES ARE INVARIABLY MANY TIMES HIGHER THAN THE NATIONWIDE RATES — AS WE POINT OUT. WE THINK THAT THESE RATES ARE THE ONES THAT SHOULD BE USED BY NGOS FOR ADVOCACY — INDEED NGOS HAVE TRADITIONALLY DONE THIS — WITH REFERENCE TO MORTALITY IN PARTICULAR AREAS BEING — SAY ‘FOUR TIMES THE EMERGENCY THRESHOLD”.

VH: And even the wording, “mortality rates decline in wartime” almost sounds (if one doesn’t read on) as though mortality rates decline ‘because of’ wartime, rather than the intended ‘in spite of’ wartime. A careful reading of the report resolves most of these issues, but I still find the notion and the comparison of national statistics and conflict zones misleading.

I see that the final section of your overview deals with the importance of getting the tolls right, partly because of the risk that aid (and other forms of attention I assume) will not be allocated according to need. A valid point, but in reality, aid is very rarely (if ever?) allocated according to need to begin with

AM: WE AGREE — AND SAY SO. POLITICS AND THE CNN EFFECT ARE THE CRITICAL FACTORS A LOT OF THE TIME…

VH: – which is probably why NGOs tend to inflate need assessments and arbitrary death toll estimations, to try to get allocations more in line with needs. Conflict scale (death toll) has next to no recognizable relationship with aid, media, and other forms attention to conflict.

This is what really disturbs me, and where my research is directed. The results of your report notwithstanding, the point is that people who knew (policymakers, media, NGOs, a very small part of the public, academia), believed/thought that each death toll the IRC produced was the best estimate, up to the 5.4 million mark. It was, after all, unchallenged until your report, and the numbers were reported each time fleetingly in the newspapers. The general public did not know (the media hardly touched the conflict), but those in a position to do something certainly did, and yet nothing happened. People/institutions were told 5.4 million people had died, had no reason to disbelieve, and yet serious responses (or even indignation) did not arise.

AM: ACTUALLY US AID INCREASED DRAMATICALLY AFTER THE FIRST REPORT’S RESULT WAS PUBLISHED, AND THE PEACEKEEPING OPERATION IS NOW THE BIGGEST IN THE WORLD

VH: I go through what I think are the reasons for this in my book, but I continue to scratch my head regarding what can be done to try to change this situation.

AM: AGREE THAT THIS A HUGELY DIFFICULT PROBLEM — BEYOND THE SCOPE OF OUR REPORT.”

I followed up with this response:

VH: “Thank you for the responses to each of my points.

The points of US aid increasing after the IRC death toll figures were released and the peacekeeping operation now being the largest in the world are duly noted.

By the same token, whether the death toll figures announced were 500,000 or 2,000,000, I think they probably would have resulted in a similar response. Much was made, for example, of the death toll figures on Darfur in 2004 (30,000, 50,000 and so on), and then in 2006 (400,000). The figures were met with great concern and mobilized resources, but few seemed to realize that the ‘known’ death toll for the DRC at the time was some 80 times greater. The DRC figures may have prompted an increase in aid from the USA, but I am skeptical as to whether there would have been much of a difference had the figures been considerably lower. Whether a conflict is a stealth or chosen one is a much greater factor, and the death toll figures are used to add weight to the attention that a conflict already gets.

This is not to take away from your point (with which I agree) that death tolls should be as accurate as possible – the 400,000 figure for Darfur damaged the credibility of the attempt to raise attention when they were found to be inflated.

In terms of the size of the peacekeeping operation, MONUC, I am skeptical on how much this had to do with the announced death toll figures. When the DRC conflict officially ended, there were still only about 4,000 troops there, and yet the ‘known’ death toll was already 2.5 million. The increase to its current levels was a very gradual process over a number of years (perhaps more to do with the sheer size of territory to be covered combined with mission creep?). Furthermore, although it may be the largest peacekeeping mission in the world, at some 20,000 or so, it is roughly one-third of the size of the NATO force that was deployed to tiny Kosovo, which in square area is about 200 times smaller than the DRC.

While I agree that much care needs to be taken in producing accurate death toll figures, and that death toll figures should not be inflated to attract attention where there is apathy, whether the death toll for the DRC is found to be 500,000 or 5.4 million, I think it can be safely said that neither aid nor peacekeeping levels are commensurate with the levels of need.”

This is Professor Mack’s response:

AM: “Agreed that Darfur got far more coverage — and celebrities — than the DRC…

On Monuc remember — I worked for nearly three years in Annan’s office — that the UN moves at a glacial pace … This was also true of PKO in Darfur.

Kosovo demonstrates the inconsistency of major power responses better than any other case.”

So that was the discussion. I’m sure the debate will go on…